Charlie’s Story

Charlie doesn't know why. Robert doesn't say why.

Margaret's voice rings out again. "He's after you."

This is the Robert who had once poured alcohol in Charlie's eyes, tried to light Charlie's feet on fire.

Charlie, 16, and frightened again, does what he does best.

He runs.

Robert, 17, follows, chasing Charlie outside the Wilkes-Barre apartment they share with 12 siblings. Robert gets close, within 15 yards.

But Charlie's car is closer.

Under the dark of the 11 p.m. sky, Charlie jumps into the blue 1973 Camaro and speeds off; Robert races toward him, hurls rocks, tries to cut off the car.

But Robert isn't fast enough. Charlie speeds out of the complex, down Scott Street and makes a right onto Kidder. He figures he's safe as he makes the left onto Wilkes-Barre Boulevard.

Charlie knows Robert doesn't have a car. But he also knows he can't go back home, at least not tonight.

As the spring evening chill settles in, Charlie drives on, racking his brain for a place to stay.

A right on Hazle Avenue, on to Academy Street, to Carey Avenue.

He passes two elaborate churches, some stores, well-kept houses.

At the corner of New Alexander Street, there's a convenience store. Charlie notices a pay phone. He stops the car.

Here, large trees shelter most of the road, and manicured lawns display brick or sided houses with lively back yards.

It's a world apart from Robert and the rest of Charlie's family.

He picks up the phone.

Charles DeGraffenreid was born Dec. 7, 1959, to Mary Margaret Elizabeth "Noon" DeGraffenreid-Wade and Robert Wade, in Wilkes-Barre.

Noon was a homemaker, struggling to care for her 14 children and, eventually, some grandchildren, all under the same roof.

Wade, the father of seven of the children, drove trucks occasionally, but earned most of his money through bootlegging, selling bottles of Boone's Farm, a cheap wine, and other liquor.

Charlie saw little of Wade growing up.

Some of Charlie's brothers and sisters turned to crime: pimping, prostitution, drugs, burglary, assault. Newspaper accounts show offenses spanning three decades involving at least five of Charlie's siblings. The only way a DeGraffenreid seemed to make the paper was for a crime or tragedy.

"It was there, but you hide it from the little kids," says Charlie.

"I don't like talking about it. I know they were go-go dancers."

Charlie's youngest brother, Tyrone, drowned in a swimming pool on Aug. 12, 1971. Charlie went to the hospital and saw his mother holding the dead boy in her arms. She sobbed hysterically, unable to accept what had happened.

Nearly four years after the drowning, the 12-room, two-story DeGraffenreid home at 125 Lehigh St. in Wilkes-Barre was struck by fire. It started in one of six second-floor bedrooms and spread to other rooms and the attic. No one was harmed, but the family had to move.

"I had two nice pairs of pants," Charlie says, "and they were covered with smoke."

As children, the DeGraffenreids moved around Wilkes-Barre often, but a change of address never guaranteed a better home. Only the house numbers stick in Charlie's mind. He tries to forget the rest.

He remembers one, though, where Heritage House Stands on Pennsylvania Avenue. "That place was the pits, man," he says. "Roaches up and down the place."

Surprisingly, one of Charlie's few fond childhood memories involves brother Robert. Their mother made a pair of small, wooden stands for them to shine shoes downtown. At 25 cents per shine, they sometimes walked away with $20 - a fortune for a child, but a pittance for such a large family.

Charlie also fondly recalls his time on the Heights Packers mini-football team. It was one of his mother's few joys, watching one of her sons do well at something.

"She didn't know much about the game. She just knew that I was doing good."

Mini-football put him on a path to greatness in sports. By 10th grade, he was a star athlete at Meyers High School - known as "Charlie D" in the hallways and in newspaper headlines.

Still, success as a member of Meyers' football, wrestling and track and field teams did nothing to lessen Robert's contempt for Charlie.

"You've got to understand how tough this guy was," Charlie says. "I was like one of the best wrestlers in the United States. Where does that leave him if he can deal with me?"

"My brother's trying to kill me," Charlie hollers into the pay phone. "Mrs. Wysocki, you've got to help me."

"Where are you?" she asks.

"Right around the corner."

"Come over to the house."

Charlie knows Patricia and Stan Wysocki will help.

He remembers their kindness. He remembers how their son Steven befriended him when he transferred from GAR High School to Meyers in eighth grade.

Charlie also remembers how he looked out for Steven, who was the same age and also active in sports.

He remembers how the Wysockis invited him to their Charles Street home for dinner after Charlie won his first District 2 wrestling title as a sophomore.

He remembers that Steven went looking for him when he didn't show.

An offer from Steven echoes in his mind: "If you want to start coming over, just let me know."

To have any chance in life, Charlie knew he had to get away from the DeGraffenreids - for good.

Standing at the pay phone on that cool spring evening in 1976, that's what he decided to do.

The first night, he slept on the Wysockis' pullout couch.

Before long, Charlie had his own room.

The Wysockis, a white family, were colorblind at a time when many people in Wilkes-Barre couldn't see past race.

"My son asked if he could come over and told me, 'But dad, he's black.' We said we didn't care," Stan says. "It was an issue with certain people, certain neighbors, but we didn't care.

"I had some black friends ... and the guys used to kid me, 'Hey Stan, I'm going to send my son down to your house. Will you take care of him for me?' "

Stan ran a successful masonry contracting and swimming pool business. His wife later opened a sporting goods store in Wilkes-Barre. The Wysockis provided for Charlie, in addition to their biological children Steven and Millie, in a way Charlie only dreamed of when living with the DeGraffenreids.

"Everything was made easier for me. People, they gave me respect. I never wanted anything and never had to get anything because it was there."

That doesn't mean things always went smoothly. Charlie had a difficult time adjusting to a curfew and spending more time on schoolwork. The Wysockis hired tutors for Charlie.

He also faced other pressure.

There were rumblings from some in Charlie's native Heights, from people who believed the Wysockis stole a promising black athlete from the DeGraffenreids.

"My oldest brother (Leroy) told me I better go home. All Leroy was worried about ... was getting money out of me. He saw me at football games. He said one thing and the Wysockis said another."

The opinion that counted the most, however, came from Charlie's biological mother. She told Patricia that Charlie would be better off with the Wysockis.

The conflict ate at Charlie, but it didn't hinder his integration into the tight-knit South Wilkes-Barre community. At the time, it was a place where success on the football field, or on the wrestling mat, turned 16-year-old kids into idols.

"He was a great fit at Meyers because he was an outstanding personality," says Coughlin assistant principal Andy Kuhl, a classmate of Charlie's and fellow member of the football and wrestling teams.

"As time went on, we all came to realize that athletically he was something special. But he was also a big part of the school community ... not like a person that sometimes becomes isolated."

Some in the Heights told Charlie he shouldn't go to Meyers and play for legendary football coach Mickey Gorham.

Charlie had been told Gorham didn't like black players, but Charlie wanted to find out for himself.

Gorham, who met Charlie while he still lived with the DeGraffenreids, ended up the opposite of how he had been portrayed.

He gave Charlie special attention, buying him decent shoes and making sure he ate well. Gorham once took Charlie to dinner with him and his wife on their anniversary.

"He was one of the toughest athletes I ever coached," says Gorham. "He never got hurt in high school. You couldn't hurt Charlie."

Charlie offered an inkling of the athlete he would become at a football camp at Pine Forest during the summer before his sophomore year in 1975. Charlie ran over, around and past players his age and older.

"You got to see Charlie against a lot of other guys from around the area that were the best and he stood out," Kuhl says. "We just knew. He had the package. He was big, strong and fast."

By the end of the 1977 football season, Charlie's senior year, he broke school records for career rushing yards and touchdowns set by Mickey Dudish, two years Charlie's elder and the starting fullback at the University of Maryland. Charlie was just as untouchable on the wrestling mat. There he competed one-on-one, with no help, the same way he had spent the first 15 years of his life.

As a wrestler, Charlie sometimes had to lose weight and regain it quickly to fit into the Meyers lineup. He could do that well, especially when he had to get heavier.

"My memory of Charlie eating is a blur," Kuhl says. "I was afraid for my fingers. ... He probably still owns the record for pizza."

By the time he won his third District 2 wrestling gold medal and the Class 3A state title at 165 pounds his senior year, Charlie had drawn the attention of more than 100 colleges.

Charlie knew that without the Wysockis none of this would have been possible - or at least it would have been much more difficult.

"He wanted to make sure everything would stay the way it was," says Kuhl. "A lot of times, we'd be driving home from a wrestling match, we talked the whole way home ... times like that he opened up and was really happy about where he was. I think he always appreciated what the Wysockis did for him."

By this time, the Wyosckis took guardianship of Charlie. They eventually adopted him.

Planning for college, Charlie made visits as far away as Wyoming. But after visiting Dudish at Maryland, Charlie liked what he saw and accepted a football scholarship there.

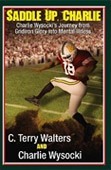

He signed his name on the national letter of intent as Charlie Wysocki.

Charlie D. was no more.

Charlie's talents easily translated to the next level. He played little in 1978 as a freshman, but he broke out as a 5-foot-11, 200-pound sophomore. He replaced career rushing leader Steve Atkins, a fourth-round selection of the Green Bay Packers in the '79 NFL Draft, at tailback in Maryland's I-formation attack.

"Once (Atkins) left, that was it. Charlie ran the ball every damn play from then on," says Lackawanna College football coach Mark Duda, a Wyoming Valley West High School graduate who was a freshman defensive lineman at Maryland in '79. "As far as toughness went and durability, he was unmatched.",/

Charlie surpassed the 1,000-yard mark that sophomore year, helping Maryland to a 7-4 mark under coach Jerry Claiborne.

Charlie's toughness really showed as a junior. In a game against North Carolina, he was getting the bulk of the carries, as usual. On one play, Charlie was met head-on by a future NFL Hall of Famer, linebacker Lawrence Taylor.

"LT hit him a ton and practically killed him," Duda says. "(Charlie) got up, went out for about four plays and came back and ran the ball 25 more times. His ability to cope with adversity and physical pain, he had no equal."

Why? Perhaps because Charlie had already dealt with so many problems as a kid.

When he ran the ball, Charlie mourned his dead brother, Tyrone. But he also thought about the bright future ahead, how his new mom took a chance on him, how she was the only one who believed in him. He wore the St. Jude medal she gave him, pinned to his shoulder pads.

Against Duke in 1980, Charlie carried the ball a school-record 50 times.

His speed - he reportedly ran a 4.6-second 40-yard dash in high school - was not as remarkable as his toughness, his ability to absorb hits, elude tacklers and run over defenders.

All that, and Charlie didn't train much. He ran - some said he could run forever - but didn't lift weights often.

Charlie had hit his stride. To top it off, he had a chiseled body, good looks, bright smile and unforced charisma.

"He'd give good interviews. He was an intelligent kid," says former longtime Maryland sports information director Jack Zane. "He was very popular with the team and students. Some players just get cheers running out on the field. He was in that category."

Maryland ended the 1980 season with a 35-20 loss in the Tangerine Bowl to Florida and wide receiver Cris Collinsworth, who enjoyed a stellar NFL career with the Cincinnati Bengals and now broadcasts NFL games for FOX.

Charlie, who ran for 159 yards, and Collinsworth were named their respective team's Most Valuable Players.

Entering the 1981 season, Charlie reached the pinnacle of college football. Having set several school rushing records his junior year, Charlie was a legitimate candidate for his sport's top honor, the Heisman Trophy. He went on a promotional tour with legendary ABC broadcaster Keith Jackson and other Heisman front-runners, such as Southern California's Marcus Allen, prior to the season.

Charlie's life story garnered attention from MGM and Columbia Pictures. They wanted to do a movie about his life. All the story needed was a happy ending. Many, including Charlie and the Wysockis, expected that to come on April 27, the start of the 1982 NFL Draft.

Against Vanderbilt that senior season, Charlie bulldozed toward the goal line for a 10-yard touchdown run, his second of the game.

As Charlie crossed the goal line, a Vanderbilt defender hit Charlie and grabbed his Charlie's left ankle.

Charlie heard it before he felt it.

Pop!

He fell to the ground, overcome by the most severe pain he'd ever felt. The sprained ankle forced Charlie to miss two full games and parts of two others.

"There was no cause for it. It was stupid," says Charlie. "He twisted it on purpose."

Although the ankle and some irksome problems with insomnia hampered Charlie for a time, Charlie appeared to regain his form by the end of the '81 season. In his last college game on Nov. 21 he ran for 153 yards in a blowout victory against Virginia. He finished his senior season with 715 rushing yards and left Maryland with ownership of most of its rushing records.

Still to come, many predicted was that happy ending - the NFL Draft.

No one could miss this party.

No one who knew Charlie. No one who knew the Wysockis, or coach Gorham or, for that matter, the whole of Meyers High School.

It's Tuesday, April 27, 1982, the first day of the NFL Draft. The Wysockis' South Wilkes-Barre home is the stage for the celebration of Charlie's anticipated selection by a professional football team.

Mrs. Wysocki cooks up a storm, including Charlie's favorite, lasagna. Close to 300 people come and go. They saunter in and out of the house and spacious back yard. There is plenty of food, music and anticipation. By 10 p.m., with about 100 guests still waiting, there's also some worry.

No team calls Charlie's name.

"This is good for me. It'll make me hungry," Charlie said at the time, awaiting the second day of the draft.

By noon Wednesday, 335 college players are chosen. But not Charlie. He retreats silently to his room.

Still, several NFL teams are interested, including the Dallas Cowboys. Like so many football fans, Charlie is enamored with "America's Team."

The next day, a Cowboys representative visits the Wysocki home with a free-agent contract in hand.

"Charlie had that explosiveness getting through the line," says Zane, the former University of Maryland sports information director. "At 40 yards he wasn't that fast. ... But the NFL had a book, if you don't meet this test, that test, they'd just automatically move you down the line."

The Washington Federals of the fledgling United States Football League also were interested, but didn't offer enough money, Charlie says. The NFL's Kansas City Chiefs were set to fly someone to Wilkes-Barre the morning after the draft with $15,000 and a contract.

Even though Dallas already had 1977 NFL Rookie of the Year Tony Dorsett, Robert Newhouse and Ron Springs in the backfield, Charlie signed with the Cowboys for a $2,000 signing bonus.

"He did have a guaranteed contract with Kansas City. I tried to talk him into it, but I couldn't talk to him," Stan Wysocki says.

"I was sitting at a table here and the Cowboys kept feeding him a lot of malarkey and I knew it was, and (coach Gorham) was here but we couldn't do anything."

No one could have known that Kansas City would have given Charlie the best opportunity to play. Joe Delaney, the Chiefs' star tailback, died a little more than a year after the '82 draft while trying to save three drowning boys.

Charlie went to Dallas to work out a month before training camp started in the summer. Like the previous fall, however, he couldn't sleep right. It reflected in his performance and after just a week of camp, Cowboys coach Tom Landry cut the tired, confused bull of a young man from Wilkes-Barre.

Disappointed, Charlie put football on hold to go back to Maryland and try to complete the 18 credits he needed to graduate with a degree in communications and recreation.

Charlie tried to relax, focus elsewhere, on his schoolwork. Charlie tried to rest. Charlie tried to sleep.

But he couldn't.

Soon he would be running again.

It's a cool evening and a bloody Charlie Wysocki is in wide-open space on another long run.

Just an hour before, he had been sitting in his adoptive parents' home. His father had told him everything would be OK, but Charlie knew something was up. He knew it was time to run.

Into the car. Three six-packs from the bar. Guzzling. Driving. Guzzling some more. Forty miles down I-81 South. Off at Frackville. Out of the car.

He breaks a beer bottle against the car.

He pulls the glass across one wrist, then the other.

He has failed, he tells himself. Something is wrong that he can't figure out. It's bad, though. There's no cure.

Minutes later, he doesn't really know why, he's back in the car, pulling into the parking lot of the Schuylkill Valley Mall. He can't think straight, but he tells himself not to go in the mall bloody.

For some reason, he figures he'll be OK slinking into a seat at a nearby McDonald's. At least it's warm.

He tries to think straight, but sees himself lying on a slab in a coroner's office. He tells himself, "No. I don't want to go out that way."

No one bothers him in the restaurant, but Charlie can't sit still. He heads back outside to his car. He's not there for a full minute before state police cars swarm.

Troopers level their guns at the unstoppable former star running back from Meyers High School.

Charlie's confused. He's lost his will to live, but he's also lost his will to die.

The cuts on his wrist aren't deep enough. He thinks to himself: Please don't shoot.

Even though the fledgling Washington Federals of the USFL had offered Charlie a contract, being cut from the Dallas Cowboys was too much for him.

Former Maryland teammate Mark Duda heard about it while in training camp for his senior season.

"Charlie's not doing so well," Duda is told.

"What do you mean?"

"He's not taking being released so well."

"Well, nobody takes it well," says Duda.

During Charlie's previous four years at Maryland, he had called his adoptive parents, Stan and Patricia Wysocki, up to three times a day. Upon his return to Maryland to finish the remaining semester of classes he needed to graduate in the fall of 1982, Charlie stopped calling. When his parents reached him on the phone, he offered nothing more than "yes" or "no" answers.

"When I look back, it was like putting a Band-Aid over it," says Patricia. "It cheered him up for a few minutes."

When he called his parents on the morning of Oct. 19, 1982, Charlie couldn't speak.

"I was on the phone for 35 minutes," Patricia says, "and all he kept saying was 'Ma.' He never said another word. ... He just couldn't bring anything out."

Charlie drove back to South Wilkes-Barre. He didn't stay long before trying to kill himself.

"The way he talked ... he was slurring his words and the things he was saying didn't make sense," says Stan. "He told us he couldn't sleep."

That would be the least of Charlie's problems.

After police in Frackville arrested Charlie outside the McDonald's, they called the Wysockis.

"I thought they were going to tell me (Charlie) was dead," says Patricia.

Released to the custody of the Wysockis, Charlie was taken to General Hospital in Wilkes-Barre. When the car stopped, he tried to push his father out of the car and take the wheel so he could get away again. Shortly, he was transferred to First Hospital of Wyoming Valley, a private institution on Dana Street in Wilkes-Barre.

The wounds on his wrists would heal, but some mental scars remained. They led to a life-threatening diagnosis.

At the time, the American Psychiatric Association had recently updated the term "manic depression" with bipolar disorder. The new terminology stressed the highs (mania) and lows (depression) of the disorder.

The jargon was lost on Charlie. He was confused. He just knew he wasn't right.

He didn't speak again for six months.

The Wyosckis took Charlie to a psychiatrist three to four times per week at $90 a session. Stan Wysocki suggested taking Charlie out of the house for exercise, maybe to Kirby Park to run.

Patricia had to lift Charlie out of the chair to get him moving. It was not an easy task. Charlie had already gained nearly 30 pounds on his 200-pound frame.

Around Christmastime of 1982, Charlie slipped into a catatonic state. His brother Steve carried him to a Christmas party at sister Millie's home. They fed him and showed him presents, but Charlie showed no expression. On Jan. 6, the Wysockis took Charlie to Philadelphia Hospital.

There, his bipolar diagnosis was confirmed. A doctor told the Wysockis Charlie would never be the way he was. The Wysockis thought that meant Charlie would just be "slower moving."

"I never thought it would take that long," says Patricia.

Charlie remained catatonic for six months until April 1983, when, out of the blue, he called his mother on the phone.

In a 90-minute conversation, Charlie recalled the Christmas gathering at his sister's, the gifts and food. Before long, Charlie returned to the Wysockis' Charles Street home in South Wilkes-Barre. Still under contract with the Federals, Charlie began working out with the Pocono Mountaineers, a new local semi-pro team. But he no longer looked or felt like the tough, strong young man who could run forever. He looked broken, soft, vulnerable. He barely played.

Charlie became more functional, but that led to more problems.

He sent 21 bouquets of flowers to the coaches' secretaries at Maryland. He ran up a $1,200 phone bill. And worse, much worse, Charlie repeatedly tried suicide.

Stan was an avid hunter and kept his guns in the attic. One day, Patricia noticed the attic drop-door was down. Charlie, she reasoned, must have gone up there to look for his father's guns. Fortunately, Stan already had considered this possibility and removed the weapons.

On another day, Patricia tried to get Charlie out of bed and dress him. She mustered all her strength to pull Charlie into an upright position, and underneath his body were dozens of red pills. Fortunately, the capsules were harmless - they were a supplement taken by Patricia for her fingernails.

One time, Patricia tried to open the door to Charlie's room, but it was locked. Hysterical, she pounded on the door and screamed for her husband. Stan rushed upstairs and managed to force the door open. Inside, Charlie had one leg out the window, about to jump.

"We had to foolproof the house," says Patricia.

Many offered theories as to why Charlie's mental illness surfaced. The first, and most obvious? The letdown of not being drafted.

"On the second day (of the draft), I'm thinking, 'Damn, all this over a sprained ankle,' " says Charlie. "That guy who did that to me, if I had a gun I'd shoot him. He gypped me out of my career. Now I'm dealing with this stuff."

Another was the pressure Charlie felt to succeed in football. In what other occupation could Charlie feel as much support, as much pride and as much love?

Additionally, Charlie found himself torn between two different worlds at such a young age - the poor, black DeGraffenreids and the well-off, white Wysockis.

"People say it was the pressure of the draft, but the bottom line is, I don't know what happened," says Duda.

Most likely, the bipolar first presented itself in the form of sleeplessness, which Charlie initially experienced at Maryland around the time he injured his ankle early his senior year. Experts say a "trigger" event usually sends those predisposed to bipolar over the edge.

"That would have been a clear indication that something was wrong," says Dr. Robert Yager, who would treat Charlie starting in July 1996. Yager said that on a scale of 1-10, the severity of Charlie's bipolar would rate a 9 when he displayed symptoms.

"One of the aspects of sleep deprivation would be psychotic symptoms. ...

That wasn't something they were looking for."

No one looked then because Charlie, with his big smile, easy-going demeanor and friendly attitude, never exhibited any signs of being disturbed.

One man who would have noticed is Duda. He spent plenty of time with Charlie, including those long rides from Maryland back to the Wyoming Valley during college breaks.

"Everybody in that car, every one of us," says Duda, "was more likely to do something crazy than he was.

"He was nice to every damn soul in the world."

Andy Pappas, a psychiatric aide, walks into the admissions ward at Clarks Summit State Hospital one day in the winter of 1984.

The ward holds new patients. Workers have no idea if the newcomer is homicidal, suicidal, has AIDS, or just wants to punch somebody.

Having worked the ward long enough to become somewhat desensitized, Pappas, on the night shift, still isn't prepared for what he is about to see.

There's that guy that he used to watch score touchdowns in high school and college. He sees Charlie, but can't believe that it's really him.

Charlie's in what's called the quiet room. It's anything but when it holds the hulking, angry, ex-football star.

The room's got padding, windows with screens and a heavy door. Charlie rams his body into the walls and doors much like he threw himself into opposing defenders. The only difference is Charlie is now close to 300 pounds.

Pappas can hear the repetitive thumps. The echoes are loud enough to be heard throughout the building.

Charlie defecates in the quiet room and smears it on the walls and himself. Someone orders the aides to shower him, but no one wants to touch him.

Pappas thinks it can't get any worse than this.

Charlie would go in and out of the doors at Clarks Summit 15 more times. He walked the grounds naked sometimes, urinating wherever he pleased.

Sometimes he stayed for as long as a year, sometimes for just a few months. Charlie usually re-entered Clarks Summit during football season.

Sometimes he stayed out of the hospital for months at a time - enough time to start a family.

In 1981, he met a woman in a local night club and they lived together off and on for about seven years. She bore him a daughter, Tiffany, in 1984. In April 1988, they married. Charlie and Donna Wysocki divorced twice, for the final time in 1991.

Donna refused comment for this series.

Charlie's bipolar behavior presented itself mainly in the form of delusions. He told police in Pittsburgh he was an FBI agent. He entered through the back of the Kirby Center and hopped onstage during a religious revival show and began to sing along.

He also hopped onstage at a strip bar in Los Angeles. Dancers ran scared while he made drinks and took money from the cash register.

"Hollywood's finest," as Charlie referred to the LAPD, arrested him and put him in leather shackles, one of which he broke through. They took him to Camarillo State Hospital, another mental institution.

Outbursts occurred when Charlie didn't take his medications. He would adhere to doctors' orders for a little while, but once he felt good, he would stop. The Wysockis found pills meant for him in a crevice of the fireplace.

No pills, in time, meant more grandiose thoughts and run-ins with Wilkes-Barre police. He called local newspapers to tell them he was training to be the first barefoot linebacker in the NFL. He told friends he was working on a multimillion-dollar deal with Donald Trump.

"He had all these huge ideas, things that were just, you knew he didn't have control over what he was saying," says former Meyers classmate Andy Kuhl.

"You couldn't do anything but sort of go along with him and say to yourself 'I hope this ends soon.' "

Shortly after Charlie's second divorce he found himself at a McDonald's in Dickson City in the summer of 1991.

It was there his life would take another sharp turn. And like nearly 15 years before, he would find care and comfort with a white family.

A woman named Lois was ordering food with two of her sons. Her boys, Philadelphia Eagles fans, started talking with a black man in a Dallas Cowboys jacket and hat. Lois didn't think much of it, except the boys seemed to enjoy the conversation.

"They didn't realize they shouldn't give him our phone number," Lois says. "He kept calling ever since."

Charlie developed a relationship with Lois (she declined to give her full name for this story) and her family. Charlie and Lois were married in May, 1994. It was a marriage not of romance but care-giving love, according to Lois.

"Charlie is the age of my children," says Lois. "I still feel like his mother, like I take care of him."

During his early time with Lois, Charlie recorded his most intimate thoughts and memories on a mini tape recorder. Lois learned more about Charlie than she knew about herself.

"You can see his heart," says Lois.

Three months after the marriage, Lois encouraged Charlie to go back to Maryland to finish his degree. She helped Charlie get accepted via a program for former athletes. The university seemed happy to have their former big man on campus back.

Lois was concerned, however, that Charlie wouldn't take his medication. It wasn't more than a few weeks before someone called the police on Charlie again. He was yelling and screaming uncontrollably on campus.

Charlie, crying, called Lois, who rushed to the mental ward of the Maryland hospital where police had taken him. Charlie was shackled with rubber cuffs to a bed. Just a little while before, he had broken out of the cuffs.

Three female patients had been walking down the hallway. Charlie managed to get to the doorway and punched each of the women. A male nurse came running to help.

Charlie hit him too. He knocked him down.

Finally, a big security guard managed to restrain him.

"I wasn't right. I shouldn't have done that," says Charlie.

The hospital wanted Charlie put away for life. Someone told Charlie one of the woman was hurt badly. Lois, however, called a Maryland law professor who helped Charlie get released to her custody.

When he returned to Lois' home in the Honesdale area, Charlie improved. Lois monitored his medication intake and Charlie complied. Charlie secured his own apartment in nearby Hawley and managed to stay out of the hospital for two years.

In March of 1996, Charlie went back to Clarks Summit for two months for a check-up of sorts. When he was released, "partial remission" of the bipolar was written in his discharge notes.

After a nearly four-month stay starting in December that year, Charlie experienced the most successful period of his battle with mental illness. The only negative? He became estranged from the Wysockis.

Stan and Patricia were tired. They had spent so much time and money on Charlie - furnishing new apartments for him only to see Charlie give his new belongings away, arranging for private doctors and treatment and countless drives to hospitals and police stations - only to see Charlie disappear from them whenever he thought he was cured.

Charlie acknowledges it was his fault - falling out of touch with his adoptive family.

Lois feels differently.

"It's obvious God created him a black man," says Lois. "I think whatever we are, we should be the best, and Charlie got into trouble by wanting to be a white man."

Charlie responds: "I am black. I'm just a black man who likes white women. Look at Lionel Richie. He married a white woman."

Charlie's first wife, Donna, and other former girlfriends, were also white.

"You started out as a champ with the DeGraffenreids and got really messed up when you left," Lois told him. "DeGraffenreid, that's what you really are."

Charlie spent all of 1998 and most of 1999 living in a room at Lois' home. Lois, however, started working 18-hour shifts at a Honesdale hospital. Meanwhile, her mother began suffering from Alzheimer's.

There was little time left in the day to monitor Charlie and his medications. When she returned home from a long day, she found the pill box she left for Charlie still full.

"It was too much," says Lois.

The two divorced.

There was no place for Charlie to run to now, except back to the hospital he came to know so well.

Charlie leans heavily on a table, hovering over a young female student inside the Stark Learning Center at Wilkes University.

He's wearing a gray suit and sharp brown shirt. It's one of the few times in the past 20 years the ex-football star is dressed up.

The woman looks up and, with some caution, asks: "Do you remember the manic states?"

Charlie looks down for a moment - his trembling hands are steadied by the weight of his 300-pound frame against the table - and replies: "Sometimes."

A crowd of about 30 Wilkes students, mostly from the school's psychology club, listens intently as Charlie describes what he remembers: Incessant talking on the telephone, difficulty sleeping, grandiose thoughts.

With slurred, nearly drunken diction, Charlie reads off a list of the nine different medications and 27 pills he consumes daily to treat his bipolar disorder. The Wilkes students' mouths slowly drop in astonishment as Charlie continues: "Sur-kwol (Seroquel) ... dep-ko (Depakote) ... "

"What do you do?" another student asks Charlie, who quickly moves across the room to listen because his hearing isn't what it used to be. "I want to open a soul food restaurant," Charlie says.

A male student announces his approval and Charlie rushes over to shake hands with him, like two teammates on the same page.

Charlie speaks of his recent jobs: moving merchandise for a Scranton Goodwill store and washing dishes in a University of Scranton kitchen. The Goodwill closed and Charlie wasn't thrilled about getting Palmolive hands. He's excited, though, about a possible new job:

Scooping up roadkill.

This is Charlie Wysocki, 22 years removed from a derailed football career, failed suicide attempts and a life-changing diagnosis. The former Meyers High School and University of Maryland star athlete is more than three years removed from his last stay at Clarks Summit State Hospital.

Theresa Chemlik started as an intensive case manager at Tri-County Human Services on Dec. 5, 2000. She opened a folder in her Carbondale office that contained a pile of records of her new patients, or "consumers," as they're referred to in the mental health field.

Chemlik read Charlie's file, easily the thickest in the heap.

"I was mortified," Chemlik says. "I'm thinking, here's this very large man with a history of aggressive behavior, an ex-football player, he's going to beat the tar out of me."

That same day, Clarks Summit released Charlie.

The following day, Chemlik took Charlie to the Wyoming Valley Mall. Charlie shopped for a gift for a new girlfriend.

"He is friendly," Theresa wrote in her case notes.

The 5-foot-3 Chemlik felt at ease with the hulking man with a tattered past. Charlie was instantly soothed by Chemlik's soft voice.

"Charlie, he's just a big baby," Chemlik says. "He's all talk. I don't think he'd hurt anybody. Charlie, from the beginning, liked me."

There were no immediate goals, except to make sure Charlie took his medication. Chemlik was to be Charlie's primary link to the therapeutic services he needed and to the community into which he was to be reintegrated.

In the summer of 2001, Charlie spent more time in Marion Community Hospital in Carbondale. Behavioral, not necessarily psychiatric problems, led to three short stints. They served as a reset button for Charlie's recovery.

Most important, despite Charlie's cycle of admission into mental hospitals, Chemlik believed he could get better.

"I didn't think he was a lost cause."

Misericordia professor Tom Swartwood of Dallas worked at Clarks Summit as a part-time consultant with patients in group settings. Charlie joined one of the groups, labeled "Today's Modern Men," during his final stay at the hospital that started in late 1999 and lasted 13 1/2 months.

Charlie immediately became a leader of the group. In addition to his imposing stature, Charlie used generosity and great care when solving problems within the group.

Swartwood, about 10 years older than Charlie, remembered the former Meyers High School standout athlete, having watched him wrestle at the District 2 tournament more than 20 years ago.

"His kindheartedness was evident then," says Swartwood, recalling a time Charlie took it easy on a clearly overmatched opponent. "I think it's a characteristic of Charlie that still stands out."

By early 2002, Swartwood planned to attend the American Occupational Therapy Association's national conference in Philadelphia. He wanted to talk about the group Charlie was in. The more Swartwood thought about it, the more effective he thought it would be to bring along a member of the group.

Discharged from Clarks Summit for more than a year, Charlie was perfect for the job.

In the car on the way to the conference, Charlie rehearsed with Swartwood what he would say. The more they talked, however, the more nervous Charlie became. So Swartwood stopped talking, figuring Charlie could do well in a question-and-answer setting.

"He stood up to that microphone and before he was done, he had people almost crying," Swartwood says.

Charlie displayed a raw honesty that shocked and moved about 100 well-placed professionals, most of whom had seen all the ugliness various illnesses caused their patients.

"You don't know how much you impact people's lives," Charlie told them.

Attendees of the conference stopped Charlie wherever he went to tell him how much he moved them. Even after he left, they came to Swartwood, asking about Charlie.

"Charlie literally stole the show," says Swartwood.

For some 10 years, Charlie had wanted to speak publicly about mental illness. This proved he could. It was something else he was good at, besides football or wrestling. Or running. He latched onto it.

"I was shaking," Charlie says of his first speaking engagement. "But I feel I'm speaking the truth and you've got to make them understand."

When Charlie returned from the conference, he spoke with Jan Mroz, a regular at National Alliance of Mental Illness meetings in Scranton. Charlie told Mroz, a computer applications teacher at Valley View High School and whose son is bipolar, he'd like a video to present when he speaks. The two developed a friendship, and Mroz and Charlie produced a 20-minute film called "The Charlie Wysocki Story: Hope and Recovery - Living with Bipolar Disorder."

Charlie's favorite part of the video is the opening. As a Van Morrison song plays, the names of famous people who suffered from mental illness, Michelangelo, Patti Duke, etc., appear. Charlie Wysocki is the final name. "Mental illness" is then highlighted in red, spelled via a letter from each notable's name.

The video consists of interviews with Charlie, who talks about coming to terms with bipolar disorder, the importance of taking medications and his quality of life. Chemlik; Charlie's psychiatrist at Clarks Summit, Dr. Robert Yager; and his former boss at Goodwill, Earl Brinkman, were also interviewed.

The video became a prologue for Charlie's speaking engagements, which became more numerous over the next two years.

"We're just two Polish guys trying to help people out," Mroz joked.

Charlie speaks at alliance meetings in Clarks Summit, in Philadelphia, at College Misericordia, even at his high school alma mater just last fall.

Charlie enjoyed being back at Meyers, where he had shown such talent and promise and made a new name for himself two decades before. But in the back of his mind, Charlie felt strange.

"I really felt bad though, due to the fact that I had a shot with the Dallas Cowboys and didn't make it. People can look at it like that, 'He didn't make it, how can he tell us anything?' "

But Charlie has plenty to tell, and he pulls no punches. His life is an open book. Go ahead, just ask.

In the summer of 2003, someone did. At a weeklong camp for diversity at Misericordia, a high school student asked Charlie if he would have had a better chance of making it with the Dallas Cowboys had he been diagnosed earlier.

Charlie paused to think.

"No, I wouldn't have wanted to change any experiences I've had," Charlie explained to the student, "because it brought me to this place and gave me a gift to give to other people."

The response floored Swartwood, listening in the back of the room.

"This is a man, (football) is all he wanted in his life, and not making it was such a powerful blow," Swartwood says. "You'd think if anything, he'd like to see things go the other way. My knees buckled when I heard that. It speaks to the greatest gift he has, to give back to others."

Charlie sat in Chemlik's small office in Carbondale in February, filling out a form for a class action lawsuit for people who had developed diabetes as a result of taking certain medications to treat mental illness.

Charlie, a diabetic, believed the suit could net him a million dollars or so.

A little grandiose thinking, but it beats imagined real estate deals with Donald Trump.

Charlie talked about getting in shape to play football for the semi-pro Scranton Eagles, for whom he played sparingly as a lineman in 2000 and 2001.

"It's not playing for the Dallas Cowboys, but it's still playing," Charlie said as he sat on a couch in his apartment. Charlie knew he could still do it, even at age 44.

A little grandiose thinking, but it beats talking about playing for the Philadelphia Eagles.

Charlie is happy to be living in the second-floor apartment on Church Street in Carbondale. The two-story home is run by Step By Step, Inc., which provides semi-independent living facilities for adults with a wide range of disabilities, including mental illness.

There is round-the-clock supervision, but Charlie can come and go as he pleases, as long as he takes his medications and is respectful of his housemates.

There are a few pictures of Charlie in his Maryland uniform hanging on the wall. He keeps dozens of the hundreds of recruiting letters he received more than 25 years ago in the drawer of a night stand.

Charlie gets by on little money. He receives $590 per month from Social Security disability payments, and the Advocacy Alliance handles his money by paying his bills. Charlie's health care is covered by his Access card.

He usually eats soup or pasta for dinner. He lives simply, watching his favorite television programs like "COPS" or "Judge Judy." Chemlik takes him and other patients of hers to the movies regularly. Charlie is also perhaps the most vocal member at Revival Baptist Church of Scranton, where he attends services every Sunday.

In mid-January, Charlie was walking out the door to get some lunch. He abruptly stopped and said, "Wait a minute, I have to take my pills."

Charlie has come a long way from hiding pills in the fireplace.

"This is living, man," Charlie says. "This is living. I've got friends. A lot of good things are happening."

By no means is Charlie cured. He never will be. But Charlie's recovery, as it stands, is unprecedented.

But why now? Why is Charlie doing so well since that fall of 1982? Since the arrests? Since the suicide attempts?

For one, Charlie has grown to understand his medications, their purpose, how they affect him and the importance of taking them consistently.

"Not only did he feel empowered with the medication, but the fact he was changing his life and not repeating the pattern he had before. ... His own input into the medications he was using was very important," says Dr. Yager.

Chemicals are just a piece to solving the bipolar puzzle. For the first time, Charlie has a wide-ranging, consistent support system. It is made up of people such as Chemlik and Mroz. Charlie speaks regularly with Andy Pappas, now retired from his psychiatric aide post at Clarks Summit (Charlie still likes to talk on the phone).

Then there's a "partial" hospitalization program he attends twice a week at Tri-County in Carbondale. There, he meets with others with mental illness to talk about a range of topics and receives therapeutic services. Charlie sees a psychiatrist usually once every three months.

Charlie also attends National Alliance of Mental Illness meetings the first Tuesday of every month without fail. Because of his difficult childhood, his promising athletic career and his two-decade battle with bipolar disorder, Charlie is often called upon to speak out about his battle with mental illness. He was featured on an hourlong television program about bipolar disorder on WVIA-TV last summer.

He was one of two recipients of scholarships to attend the Pennsylvania Mental Health Consumers Association 16th Annual Statewide Conference in June in Scranton. The scholarships are awarded annually to emerging leaders in the state's mental health consumer/survivor movement.

To Charlie, it meant as much, maybe more than the scholarship he received from the University of Maryland in 1978.

Charlie's older brother Robert, the one who used to terrorize him, the one who never offered an explanation, the one who drove Charlie from his biological family, the DeGraffenreids, now lives in Norristown State Hospital, according to Charlie.

Robert spent some time in Clarks Summit State Hospital -at one time, Robert and Charlie lived on the same floor - and the State Correctional Institution at Waymart in Wayne County.

Robert's life of crime continued when Charlie's athletic career started to blossom in 1976.

Robert, it was later learned, also suffered from mental illness. Charlie said Robert suffered from several different types, including schizophrenia and bipolar.

After so many years, the pain Robert would regularly inflict on Charlie has waned. Charlie has somehow risen above it all and wants his brother to do the same.

"I love my brother. He's family," Charlie says. "When I get some money together, I'm going to take care of him. My mom would love that.

"I want my brother to get out of the hospital."

Charlie regularly calls his old high school coach, Mickey Gorham, and has visited with him on more than one occasion. Gorham has recently had some health problems, and Charlie wants him to know how much he cares about him.

Charlie is still in Gorham's thoughts.

"I pray for him all the time that he can beat this and have a productive life," the former Meyers coach says.

Although Charlie's relationship with the Wysockis had been strained for several years, the rift seems to be closing. For the past two years, Charlie visits the Wysockis on Christmas or Thanksgiving. Charlie also talks regularly on the phone with Stan, Charlie's adoptive father.

Perhaps the ideal would be for Charlie to return to the Wysocki's Charles Street home, where he found relief, solace and hope 28 years ago. But it's not realistic.

"To be honest, we could bring him home," says Patricia Wysocki, "but he's much better (where he is) because they can regulate his medications."

The Wysockis' hopes for success and prosperity for their adopted son have been whittled down to simpler dreams.

"It feels great, knowing he can fit himself into society and he can if he really wanted to push himself a little harder," says Stan Wysocki.

Perhaps more than anything, Charlie needs a job. He was at his best when driving a forklift and performing other manual labor tasks for Goodwill in Scranton, but the facility closed almost two years ago.

A job gives Charlie's life structure, something to wake up for every day. Something to keep focused on. Something to take pride in. He's had several leads: the roadkill gig, working in a sportswear store in the Mall at Steamtown, a security officer job at Viewmont Mall are just a few.

However, they don't seem to pan out.

But Charlie, ever the optimist, takes it in stride.

"For the most part, he's resilient," Chemlik says. "It really takes a lot to get him down. ... He doesn't let things bother him as much as other people would."

Charlie says everyone asks what happened to him.

Charlie's usual response?

"It was too much of a load to carry."

"It" was a difficult childhood, leaving his biological family, an untimely ankle injury.

"It" was a lost dream.

Charlie is wearing a red golf shirt with the collar up, green sweatpants and a blue Scranton Eagles visor. He's lying on the artificial turf at Lake-Lehman High School, drained by the early evening August sun.

"That's what I'm talking about," he tells the Eagles offense after a well-executed running play during a recent practice.

"Way to look it in," he says to a pass-catcher.

Next to Charlie's leg is a folder with the words "Coach Wysocki." It holds a roster, depth chart, play diagrams and nutrition guides. He has recently been invited to be an Eagles assistant coach.

Eagles head coach Dan Lamagna heard of Charlie through a mutual acquaintance and remembered hearing about him when he played briefly with the Eagles in 2000 and 2001.

"Knowing who he was, I knew he was a good person and he could bring a lot to the team," Lamagna says. "You have to take a timeout to listen to Charlie and his stories and about life.

"It's been nothing but a positive experience having him around the football team."

Charlie isn't big on Xs and Os - he played mostly in one formation, the "I," at Meyers and Maryland. But Charlie has much more he can offer.

At a recent practice, Lamagna tells his team coach Wysocki has something to say. Charlie steps forward and looks at the sweaty men.

"This is the first time I missed a NAMI meeting in three years," Charlie tells them, "because I love you guys."

The team claps and cheers wildly.

Charlie finally realizes he's never going to be a pro football star. He knows he's never going to be perfect.

And he knows he might not get everything he wants.

But he seems to have found himself. For now, he's done running.

"I want the world to know ... Charlie Wysocki's movin' in."

Now, he can teach others how to run.

And when to stop.